Matt Long celebrates a significant milestone in sports history. The location: Crystal Palace. The date: July 13th, 1973.

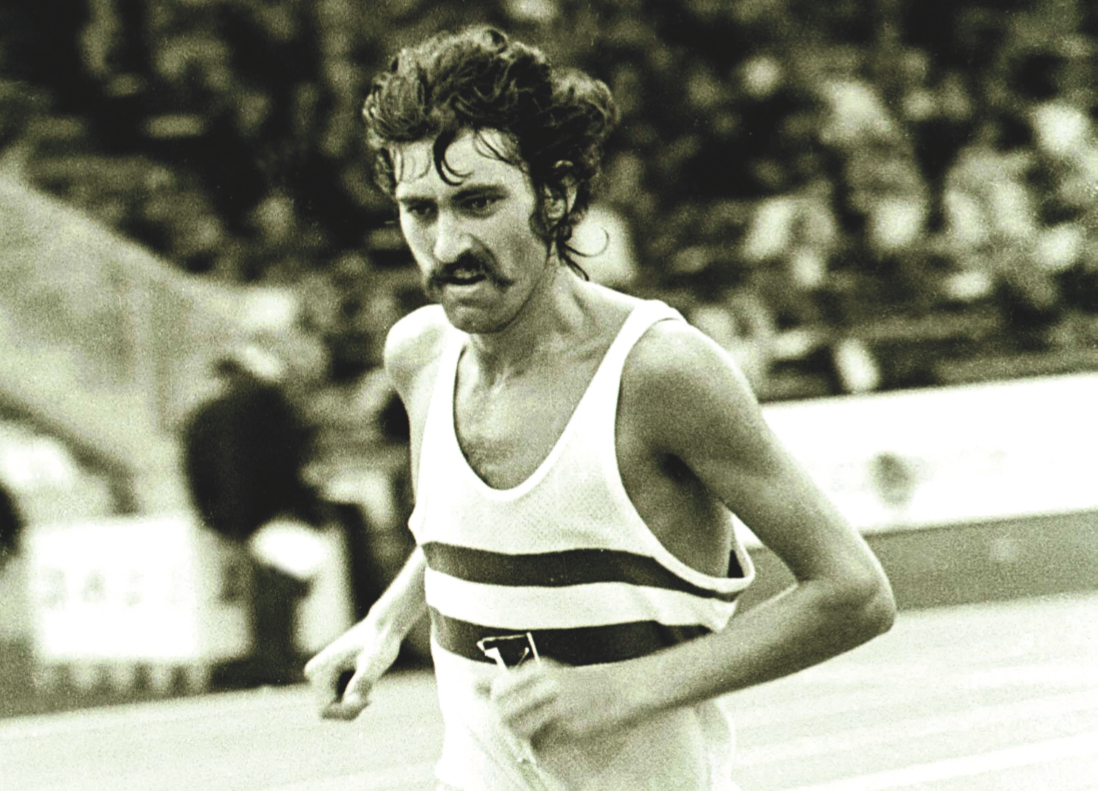

Fifty years ago today, a talented 23-year-old runner named Dave Bedford made his mark in the 10,000m final at the AAA championships with an astonishingly fast 8m08.4s opening 3000m on a Friday evening.

With determination and wearing the number 1 on his back, Bedford surged through the halfway split in a jaw-dropping 13m39.4s, outrunning Tony Simmons by just under two seconds. Simmons would go on to win a European silver medal the following summer.

As the race continued, Bedford maintained a consistent pace, completing each 1km split in 67 seconds. The spectators could sense that he was on track to break the world record set by Lasse Viren, the Olympic champion from Munich (27m38.35s).

With 1km left to go, Bedford was over 100 meters ahead of Viren’s schedule, and it seemed like he only had to cruise to the finish line to make history alongside legendary runners like Paavo Nurmi, Emil Zatopek, and Ron Clarke.

Commentator Ron Pickering shared the excitement with the BBC audience, exclaiming, “So Bedford is back in business. There’s the crowd lifting him again.”

In the final stretch, with a blistering last lap time of 60 seconds, Pickering knew the crowd was about to witness the first world record in London in 19 years. He shouted into his microphone, “The crowd is standing on their feet and roaring him on. And Bedford is back in front of his home crowd, pushing himself as he always does.”

When the clock stopped at 27m30.8s, capturing the iconic moment, Bedford and his coach Bob Parker celebrated with a victory lap, a moment immortalized by photographer Mark Shearman.

Valuable Lessons Gained

Examining Bedford’s training methods, which still place him highly on the UK all-time list 50 years later, it is easy to dismiss his intense schedule. He was known for training three times a day, totaling 3-4 hours, and covering approximately 200 miles per week.

The athletics community acknowledges that Bedford reached his peak in his early 20s, as injuries began to accumulate due to his high-volume training. Any coach promoting a similar schedule would risk having their license revoked.

Bedford once experimented by running a staggering five sessions per day, claiming to have a V02 max of 85.3, which surpassed any other athlete in the world according to the Swedish Institute of Physiology. “I am the man with the greatest oxygen capacity in the world, and I’ve got the papers to prove it,” he proudly boasted.

Guided Discovery Approach

In today’s coaching terminology, Bedford’s training under the guidance of Bob Parker can be interpreted as a form of “guided discovery.” However, it is essential not to reject Bedford’s entire approach outright, but instead separate the valuable aspects from what should be disregarded.

Lesson 1: Building Aerobic Endurance

As a young senior athlete, Bedford incorporated sessions like 12x400m, focusing on active recovery periods rather than repetition training. He believed that if your body was fit, a jogging recovery should ideally be around 65 seconds for 400m.

Bedford’s emphasis on “float” or rolling recoveries aligns with the principles advocated by coaches like Peter Thompson. These types of recoveries help the body utilize lactate more efficiently for energy, providing a valuable training stimulus.

During his teenage years, Bedford regularly included one or two fartlek sessions per week. The unstructured nature of these sessions, as recommended by coach Gosta Holmer, bridged the gap between easy aerobic runs and intense interval or repetition sessions. They worked all three energy systems without overstraining the young athlete’s body.

Lesson 2: Developing Strength Endurance

Strength endurance was a crucial element in Bedford’s training with Parker. In his late teens, he completed 15 x 200-meter hill runs, maintaining an aerobic focus. Unlike traditional hill sprints with a slow jog down recovery, Bedford’s coach emphasized the importance of the time lag between going up and down the hill. Quick descents and immediate ascents were key to perfecting this exercise.

This form of training aligns with the principles of Kenyan hill workouts and should not be overlooked as athletes transition from running hilly routes to specific hill repetitions.

Bedford and Parker were able to incorporate this mode of strength endurance training throughout the year, as it continuously builds the aerobic energy system, allowing for a larger base and ultimately leading to better performance peaks.

Lesson 3: Speed Endurance

Though Bedford’s natural talent did not lie in pure speed or speed endurance, he recognized the importance of including speed-oriented work in his training regimen.

Prior to breaking the world record, Bedford performed 2 x 6 laps at 5000m pace during the pre-competition phase of his periodization cycle. This helped create speed reserves for the longer 25-lap race.

During his teenage years, Bedford’s “speed” workouts consisted of sessions like 30 x 100m. With the benefit of modern sports science knowledge, these sessions could have been adjusted to lower volume, perhaps shortened to 60m, to minimize lactic acid build-up.

A Fresh Perspective on Bedford’s Training

Looking back, it is fair to say that a teenage Dave Bedford transported to the year 2023 would likely revise his weekly mileage target of 200 miles.

Today, he would probably focus on maintaining aerobic and strength endurance through a variety of cross-training methods, such as swimming and cycling, to reduce the impact on his body.

Furthermore, as a young athlete, he would likely be encouraged to develop his speed in the 400m, 800m, and 1,500m distances. His speed endurance workouts would involve a greater variety of training methods, including pace progressions, pace injections, and tired surges, to prepare for the demands of championship races on the global stage.

However, it is important to acknowledge that Bedford and Parker worked with the resources available to them and focused on enhancing their strengths.

Self-Reflection Questions

1. How am I developing my aerobic endurance and strength endurance to create a solid foundation for speed endurance work?

2. When should I incorporate weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises to improve my aerobic and strength endurance?

3. Why is it crucial to seize opportunities for speed development before transitioning to longer racing distances?

4. How am I monitoring the intensity, volume, and frequency of my training load to ensure a sustainable and long-lasting running career?

Matt Long is based at Loughborough University and has managed or coached for his country on 17 occasions. He can be reached at [email protected].